I Can Tell You,

I Can’t Show You

Photographers should know the rule; Show, don’t tell. I have always been intrigued by artistic images; the ones that are a beautiful composition in themselves: The standalone type of images you see at REI or on the cover of Nat Geo. I enjoy trying to capture rare moments in the mountains. I carry the camera with me each time I venture out.

More recently however I have been learning that the greatest images are part of a bigger story. Adventure photographers like Cory Rich, or Jimmy Chin present more than just a stellar standalone image. They present a story through a variety of shots that are visually diverse yet part of a bigger picture.

I wish I had known this idea earlier because when I got home from the season and looked back upon my camera roll, there was a hint of disappointment. I did not find that I shot all the right images. The story of my summer climbing season had missing pieces. The story I wished I captured and the reason I didn’t capture that story was this: much of the season was misery.

I had gone out to the Cascades to learn how to be a mountain guide. With a background in only guiding rock climbing, glaciers were unknown terrain for my climbing career. Technically speaking I had the skills with just no experience. I could pull someone out of a crevasse, navigate the mountains, set up a rope team, and teach many different pieces of the whole skillset. Pulling up stakes and going out to Washington State to guide big glaciated peaks was an experiment. It was an opportunity to expand horizons and learn.

Several months later I packed up my car and headed back home to Colorado. Shell shocked, lonely, and burnt-out, the summer climbing season had been far from my expectations.

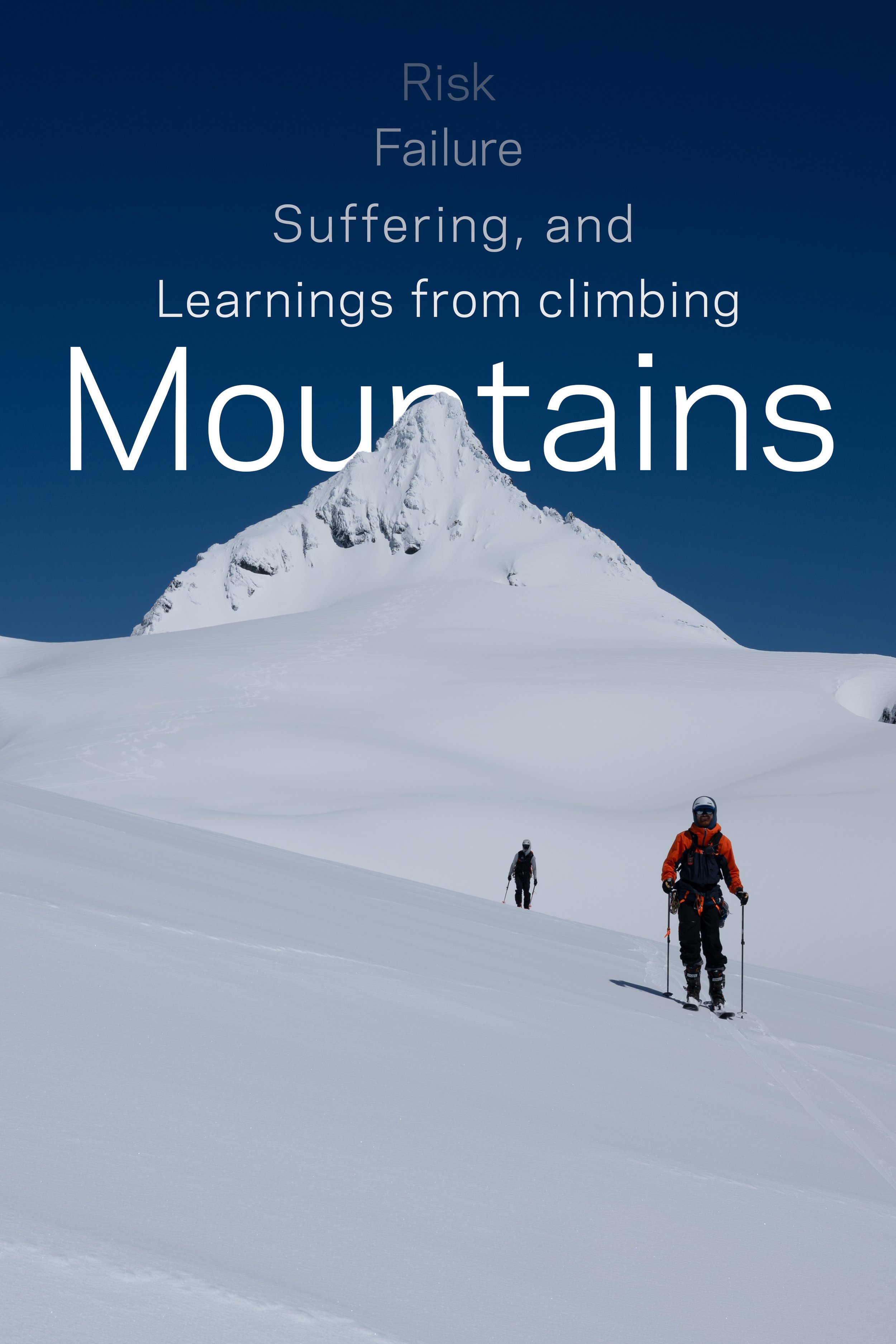

Skiers making their way up Mt. Baker on August 4th, 2024

Nikon Zf - 40mm / F/11 / 1/125s / ISO 100

I had been reading about Cory Rich and his photos. Looking back on my own camera roll I found that I had a surprising lack of images for someone who always carried a camera around. I had been so tired or miserable that I didn’t shoot with my camera as much as I should have. I learned a lesson about being a better photographer.

This lesson as a photographer led me to consider other lessons along the way. With such a hard season I found myself reflecting on what I had learned. I had to ask the questions; What could I take away from the whole experience? Was it all worth it? Could I still show a story with what I had?

To be fair there were a number of great days out on the mountain. Not all of my time in the Cascades was doom and gloom, but there are a few stories that stand out…

Base Camp Area in the Early Season

Nikon Zf - 40mm / F/10 / 1/1000s / ISO 100

IT WAS LIKE SLEEPING IN A WASHING MACHINE

Here’s the thing about rain gear; it can only go so far before you’re soaked to the bone. I have yet to find a rain layer that will keep you dry for extended periods of time outdoors. So when it was my turn to perform the solo high camp maintenance mission right as another storm was descending on the range, I was less than thrilled.

The beginning of the trek was marked by a steady rain. Several miles and thousands of vertical feet later, the rain had taken on a more horizontal orientation. When I arrived in high camp soaking wet and shivering cold, I practically dove into one of the only tents left standing in the maelstrom.

The weather was destroying the camp. As I would find out, it would only get worse. I struggled to get warm for the whole night as the wind would constantly push the tent nearly flat against the ground. Water would splatter around the interior each time a gust came through. It was like sleeping in a washing machine. It wasn’t until the early hours of the morning that the wind and precipitation would calm down. In the morning I eventually decided that movement would warm me better than my wet sleeping bag. The mountain that morning was beautiful; something that my cold stressed, sleep deprived brain wasn’t able to fully appreciate as I began to rebuild the high camp.

Looking down towards AAI High Camp the next morning

Nikon Zf - 40mm / F/13 / 1/800s / ISO 100

Interglacier below the Easton

Nikon Zf - 40mm / F11 / 1/125s / ISO 100

I WAS KICKING SNOWBALLS TO MAKE TEXTURE IN THE SNOW HOPING I WASN’T ABOUT TO STEP INTO A CREVASSE

Many new climbers have heard of the dreaded “ping pong ball” conditions. Getting caught in a whiteout in the high mountains can be dangerous. It's important to have a frame of reference in order to navigate, especially when moving through large scale terrain.

So when I was caught in such conditions as a new guide on Mt. Baker, the confidence I had built working in the mountains dissipated. I was on a new and unfamiliar mountain, navigating glacial terrain that I had very little experience with.

Whiteout conditions on the Glacier

The reality is, Mt Baker is not a complex climb. Despite the normal hazards that are encountered on Glaciated peaks, the climbing route presented a relatively straightforward way up the mountain. At the time, I did not understand that lesson as well as I could have. I had no Idea how frequently we would encounter crevasses and icefalls, or how conservative I should be while navigating them. Being caught in the whiteout in such an environment was less than comfortable.

At times there was no depth perception of even the ground around me. It was like going blind; white in all directions. I was kicking snowballs to make texture in the snow hoping I wasn’t about to step into a crevasse. Eventually I successfully guided my team off the glacier by methodically following a Gia GPS track on my dying phone.

Reflecting on this whiteout event later in the season when I had more experience made me conclude that it never should have happened. A guide who is already intimately familiar with the glacier may get away with it, but not me: a new green guide who was still learning the mountain. I slowly realized with time that I had almost left the Easton Glacier. I instead was nearly on a hanging part of the Demming icefall which is potentially a dangerous part of the mountain.

IT MADE A FLUTTERING WHOOSH AS IT SAILED PAST MY HEAD

Fresh Snowfall in the North Cascades

Nikon Zf 40mm / F/11 / 1/1000s / ISO 100

June 5th in the cascades saw a fresh dusting of new snow at upper elevations. For myself and a couple of other guides who ski, it was an opportunity for the last stellar turns of the season. We set our sights on Mt. Shuksan.

The Shuksan massif rises to 6,000 feet of prominence above the surrounding valley. The summit itself is your quintessential mountain peak that ends in a steep spire-like point at 9,131 feet. It is considered to be the most photographed peak in the North Cascades National Park and is home to beautifully skiable glaciers.

Hiking Through the rain in the morning

We chose the Sulfide Glacier route. With an alpine start, and rainy conditions at the base of the mountain, a quick, not so quick trek up to the snow line had us huffing and puffing before we had even reached the good stuff. It was the beginning of the season, and our fitness was found to be lacking. Still, after a little persistence we popped above the cloud elevation and onto a dusting of fresher snow. Where below it was dark and rainy, it was a beautiful day on the upper mountain. We were sailing above the clouds: Beautiful glacial terrain, fresh snow, and rocky spires; what more could a mountaineer ask for?

CJ ski touring below the Sulfide Glacier

Working as a rope team we toured up the entirety of the Sulfide Glacier, eying the summit pyramid of the whole time. The goal had been to ski the glacier, but reaching the summit would have been a bonus. Knowing that the warming temperature at lower elevations was our enemy, we had to debate on how much time to spend climbing up. Timing a ski mission poorly with the temperature could expose us to higher avalanche danger. Additionally the summit pyramid itself was covered in fresh rime and ice from the storm. The sun would doubtless be leading to a decay of the frozen buildup and potentially causing dangerous falling ice.

After eyeballing the summit for the entire approach, we decided to give it a go. I threw on crampons, pulled out my ice ax, and began a slow boot pack upwards. The slope quickly reaches a steep angle and I found myself wishing for a second ice ax to aid in the climb. I was about a third of the way up the summit pyramid when a piece of ice far above decided it was too warm to hang on any longer. It made a fluttering whoosh as it sailed past my head… NOPE; I keyed my radio and said “I’m calling it.”

Despite not summiting, it was a stellar ski down. In all honesty, the falling ice had not been too gnarly. We probably could have made it to the top, but our safety clock was ticking and we were tired. There’s a climbers adage: “The mountain will be there another day.”

Switching to skis after finding snow

Nikon Zf - 40mm / F2.8 / 1/200s / ISO 400

Sulfide Glacier & Mt. Shuksan Summit Pyramid

Composite Panoramic - Nikon Zf

40mm / F/11 / 1/640s / ISO 100

I WAS TRYING TO FIND IT DESPITE THE LOW LIGHT BY FOLLOWING THE DEBRIS FIELD OF GEAR

Emergency responders are sometimes a curious bunch. Often superstitious, they refuse to admit when it’s slow and refuse to say the Q-word out loud (the q-word that refers to a lack of noise.) This is what I think of when I’m reflecting on the time I said quote, “looks like the weather is lining up for us to have our first chill trip.” I should never have said that out loud.

Fast forward to the moment the expedition dome tent, where we keep all supplies necessary to constantly run trips, was ripped away from its ground anchors. The dome was gone in an instant. It was the middle of the night and I was the only person who wasn’t currently arm wrestling a tent against the wind. I chased the dome by running downwind. I was trying to find it despite the low light by following the debris field of gear. Much of what had been stowed in the dome was now splayed out in a big yard-sale on the slopes of the high camp.

There was no hope of finding the lost dome. It was gone, never to be found. Most of the gear was eventually retrieved, some of it scattered far to the glacier. The rest, including the dome itself, was lost to the mountain. The remainder of the trip was far from “chill.” We were forced to call off our Alpine start, futile efforts were made to find the dome, a climber got Dysentery-like symptoms at ten-thousand feet, and everyone was behind on sleep much of the time. Despite the rough go, we still got nine out of twelve climbers to the summit.

The Expedition Dome at High Camp

Composite Panoramic - Nikon Zf

40mm / F2.8 / 1/500s / ISO 125

Looking towards the Black Buttes

Nikon Zf - 40mm F11 / 1/400s / ISO 100

THIS TRIP WAS NEVER GOING TO SUCCEED

As a guide it was difficult to figure out how to word your messaging to a group of clients when you knew that the trip was going to fail. It’s important for me to clarify: Failure or success wasn’t about reaching the summit. It’s possible to have a successful trip without summiting. A beautiful morning in the mountains or significant gains in learning make for a successful trip. The trips in extreme weather without the opportunity to do anything except hunker down in the tents are what I would consider a failure. The worst part is it was completely foreseeable in the forecast.

On one such trip, I found myself at high camp waiting out a lightning storm. It was midnight, and I was fully dressed in my tent waiting for any indication that the storm was going to stop. It was a two day trip with three clients. For any chance at summiting we would have to leave camp at 1am at the latest, but the weather had other plans. I knew that going in; This trip was never going to succeed.

I ended up waking my climbers up at 5am. I took them on a short lived glacier walk so they would at least get to experience the mountain.

This was a repeated theme: many trips coincided with larger storms that would make existing on the mountain miserable. I found myself bracing myself for many trips knowing that a summit attempt was moot, and that we would suffer much of the time.

Retreating from the mountain the next day

IT WAS LIKE TRYING TO CLIMB A WATERFALL

Hells Highway on Mt. Shuksan

Nikon Z5 - F20 / 1/640s / ISO 100

My second attempt of Mt. Shuksan ended like the first. I found a climbing partner on facebook who was willing to try a car to car attempt on the Fisher Chimneys route. The morning consisted of a 3am wake up, a five-mile approach, and 1,000 vertical feet of 4th class rock climbing, all before reaching the upper Curtis Glacier. The Glacier late in the season turned out to be stiff and icy with plenty of open crevasses to navigate. Because of the dangerous conditions, I was placing running belays in the ice as we made our way up the steep slope of the Glacier. “Hell's Highway,” a narrow glacial corridor connecting the Curtis and Sulfide Glaciers, was no better. The corridor was steep and icy. I found myself taking my time placing screws in the ice and pickets where the snow would take one.

As it turns out, a storm the previous day had draped the summit pyramid in a layer of ice and snow. By the time we reached this section of the climb, the face was just starting to melt off. The combination of ice and warming temperatures made progress uncertain. It was like trying to climb a waterfall. I had only one ice tool with limited fall protection gear at my disposal. The cost of a misstep became too high. We were within a few hundred feet of the summit, and had to turn around.

Stopping for a smoke after deciding to turn around

Composite Panoramic - Nikon Z5

34.5mm / F10 / 1/640s / ISO 100

THE HELICOPTERS DOWNWASH SWEPT OVER US AND I COULD SEE A SPOTTER PEERING INTO THE DEPTHS OF THE GLACIER

Our descent of Mt. Shuksan characterizes the frustrations of much of my season. My climbing partner who I had found on Facebook had tried to solo Mt. Baker before our trip on Shuksan. Once on Shuksan it was clear he had a different risk perception than myself. I had been placing protection and going slow in order to navigate the glacier as safely as possible. My unnamed partner would have preferred to go fast, and possibly even un-roped.

The thing about alpine Glaciers is that their stability is difficult to gage. Venturing out onto an alpine glacier un-roped is like playing Russian roulette with a hundred chambers, and one chamber is loaded with a warhead. It's very possible to go out onto the glacier un-roped and simply find your way up and through the crevasses and icefall. But if you slip or step on the wrong place things will end very quickly for you. Crevasses are often hidden and can be hundreds of feet deep. Staring into one is like looking into the maw of the mountain.

This hazard was starkly characterized on our descent. NPS search and rescue was working on the Glacier. A rope-team of Rangers were traversing ahead of us and their helicopter was circling just above. They were there to recover a climber who had fallen into a crevasse. The Helicopters downwash swept over us and I could see a spotter peering down into the depths of the glacier. Before long, I could see one of the rangers from the rope team being belayed down towards a series of crevasses on a broken section of the Glacier.

It struck me how gray risk is. As humans we like black and white. Working in the mountains carries a decision making process that can only be gray. There I was, watching the Park Service begin to pull the body of a fallen climber from the mountain, and I was literally tied to someone with a very different, and very loose perception of risk.

That moment up on Shuksan highlighted the struggle of finding a reliable partner whom I trust in the mountains. I will always tell anyone that the hardest part about mountaineering is finding someone to do it with. My entire season had been a frustrating endeavor of failing to find people to climb with. This was compounded by the times where I was too fatigued from working as a guide.

The NPS rangers during the recovery

Nikon Z5 - 67mm / F9 / 1/1250s / ISO 100

My experiment of becoming a guide in Washington had left me tired, lonely, and burnt out. All the effort of trying to get started as an Alpine guide only to discover it might not be what I expected also produced a fair amount of anxiety. Yet despite all of the harsh realities of working in the mountains and navigating the guiding industry I found I didn’t regret it. I found that I still hunger for some adventure, and that I learned a lot from the season.

At the end of it all, I found out that I had been considered a bit of a, “black cloud.” Apparently I seemed to have gotten the worst of the conditions out of most of the other guides. One co-guide even said, “ I knew we were gonna get bad weather when I saw you were on this trip.” The trip in question did end up being pretty rough.

Despite the bad cards I drew, I still had some beautiful times in the mountains. I got to photograph the Milky Way above Mt. Baker, summit right as the sun was coming up, and enjoy beautiful moments on the Glaciers.

With both the bad and good, here are some of the things I learned:

Growth happens amidst great hardship: Struggle can bring out the best in all of us. I found that by the end of the season that I had grown more resilient; Existing in the harsh conditions of the high mountains became easier to manage. I became a tougher, more capable mountaineer.

Keep shooting: I wasn’t the only one that experienced all these hard days on the mountains, and looking at my camera roll is what kicked off my reflection to begin with. I only wish I had done more to capture some of the emotions of these hard days in the mountains. I wish I had captured the faces of some of my climbers. I should have tried to capture what it's like to rough out a storm up there. I should have been shooting even when I was miserable.

Know who you’re working for: The community of mountaineering guides are a notoriously crusty bunch. As it turns out, the specific outfit I had found work with already had a reputation for being a poor employer. Without outing them, or getting into the specifics, I definitely learned that it’s important to know who you work for, and that might mean you have to work with them to discover that they’re not the right fit.

Your physical health is more important than your paycheck: You may have heard the wisdom: “Quality Hurts Once.” When I encountered the harsh weather of the Pacific Northwest, I quickly figured out that some of my gear needed serious updating. High quality goose-down, and gloves that can stand up to the alpine are not cheap. However, pulling the trigger on these items saved me much suffering while out on trips.

A trips worth of gear. I would always lay out what I needed in the driveway to make sure I had everything. I then had to make it all disappear into my pack.

Failure Can be Success: There are still good trips that stand out in my memory where we didn’t even summit. Simply witnessing the sunrise from the alpine provides a joy for exploring the mountains. Or the days where I failed to reach my summit goal, I still learned valuable practical lessons along the way.

Risk Might be personal, but it must be a group decision: You can never eliminate risk, you can only manage how much risk you take on. While this is not a new lesson it was reinforced during my time in the cascades. Each person must decide for themselves how much risk is too much. The dynamics of this decision between climbers can also lead to friction when all the members of the party have different levels of risk they are willing to take on. It’s important to listen to each other, and be willing to make decisions as a group. Even though risk management is a personal decision, it takes a team to reach the summit.

Lastly, KEEP YOUR CRAMPONS AWAY FROM YOUR WAG BAG: I once had a ranger ask me if I would like a free WAG bag while I was applying for a climbing permit. He was asking because he could try to deny permits to those who did not know what a WAG bag was. He was sifting for people who had a lack of experience in order to lighten the load of search and rescue crews. Readers who know what a WAG bag is can quickly extract the humor of this crampons lesson. Those who don’t, probably wouldn’t have gotten a climbing permit that day.

CJ looking cool on the Glacier

Nikon Zf - 40mm / F3.5 / 1/60s / ISO 800

A rope team navigating the Easton Glacier

Nikon Zf - 40mm - F13 / 1/1000s / ISO 100

The Milky Way over Mt. Baker

Composite image - Nikon Zf - 20mm / F2 / 13s / ISO 1600

High Camp

Nikon Zf - 40mm / F11 / 1/320s / ISO 100

5am summit on Mt Baker

Nikon Zf - 40mm / F6.3 / 1/125s / ISO 400

A nice morning climbing Mountains

Nikon Zf - 40mm / F6.3 / 1/125 / ISO 400

Above the North Cascades National Park

Nikon Z5 - 33mm / F16 / 1/640s / ISO 100